Normalized Working Capital

What is a Normalized Level of Working Capital?

What is the purpose of the “normalized level of working capital” language in a letter of intent to sell a business?

The main purpose of the normalized level of working capital language is to ensure that neither the buyer nor the seller benefit, nor are either harmed, by how the business is operated from the day of signing a letter of intent until the day that the transaction is closed. Although at first glance it may not seem that way, it is intended to make sure its fair for both parties.

What is normalized working capital?

In its simplest definition, working capital is a company’s current assets minus its current liabilities. The term “normalized” is intended to take into account several factors. One, is that it is referring to the company’s financials as if they were in full compliance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) accounting. Two, is that it is referring to an average over a historical period, which could be the last three-, six-, or twelve-month periods (twelve months being the most common).

Why is the normalized level of working capital language needed and what are the adjustments for?

The reason this language is included is because transactions are typically settled on a cash-free, debt-free basis. That means the Seller retains all cash in its accounts and is required to pay off all short- and long-term debts at closing. As such, cash and debt items are typically excluded from the working capital calculation.

The reason for this is simple. If a business carries a cash balance of $1,000,000 on its balance sheet and it was included in the average of the past twelve months working capital, then the Seller would get to keep their cash at closing but the working capital amount the Seller would be delivering to the Buyer would be $1,000,000 less than the lookback period average, so the Seller would have to pay the Buyer at closing $1,000,000 to deliver the appropriate amount. This would effectively mean the Seller didn’t benefit from its cash.

Conversely a liability, such as debt, reduces the amount of working capital needed to be delivered. So if there was $1,000,000 in debt in the current liabilities on average during the lookback period, the Seller would pay off the debt at closing out of his/her proceeds. But if the working capital figure wasn’t adjusted as well, then the Seller would be delivering $1,000,000 of working capital more than the average lookback period and would then get $1,000,000 paid to the Seller by the Buyer at closing as well. This would effectively mean the Seller didn’t pay off its debt.

How do you know what the working capital is on the day of closing?

The Seller will put together estimates within a few days of closing for the Buyer to review, and if there is an anticipated excess or shortfall to normal working capital at closing, the purchase price will be adjusted accordingly up or down. Then, typically within 90-120 days after closing, a third-party accounting firm will perform a lookback to see what the actual balances for each working capital account were on the day of closing and present them to the Seller and Buyer. The Seller and Buyer then have rights to audit the figures themselves to ensure the proper calculation was done. If one party was overpaid or underpaid at closing, they will be made whole by the other party.

Why don’t we just agree and put a number as the Working Capital Target to be delivered by Buyer or Seller in the Letter of Intent?

If the company has already done a quality of earnings audit before agreeing to the letter of intent, then it might be possible. However, because most businesses don’t strictly adhere to GAAP accounting, it can be difficult to determine exactly what the “normalized” financial data should be. Some common items include revenue and payroll accruals, proper inventory accounting, pre-paid expenses, and more. The risk with trying to pick a target at the letter of intent stage is that if there are any necessary adjustments to the financial statements, it’s a flip of the coin as to whether it’s a good thing for the Buyer or a good thing for the Seller. By waiting until the buyer has performed financial diligence, and proper GAAP adjustments are known, the parties generally should wait to determining what the proper working capital balances should be based on.

Why does my working capital fluctuate from month to month over the lookback period?

There is a direct relationship between increases in current assets and cash, as well as current liabilities and cash. Without the normalized level of working capital language in a transaction a business owner would have an incentive to collect as much of its accounts receivable balance as possible, while at the same time delaying inventory purchases and payment on as much of its accounts payable as possible. Doing so would leave the company in an unfavorable working capital position at closing and would ultimately force the buyer to bring more cash to the investment in order to keep the business operating at the levels at which the valuation was based.

In isolation, if cash is going up, that means working capital is going down, unless there was profit generated during that period or cash invested. Conversely, if cash is going down from one period to the next, it means that working capital is going up, unless a loss was generated during that period or cash was distributed to the owner. However, the Seller should typically be indifferent in a cash-free, debt-free transaction with a normalized level of working capital because the Seller will be paid at closing for any cash that has been used to lower working capital, or the Buyer will use its extra cash to make the business whole for any reductions to working capital in excess of what is normal.

What does it mean if working capital is consistently going down or going up over the lookback period?

Usually when working capital is decreasing consistently over a long time, it suggests the business’s revenue and profitability is declining. Conversely, when the working capital is increasing consistently over a long time, it suggests the business’ revenues and profitability are growing. If the working capital is decreasing, the Seller may argue for a shorter lookback period, because the business doesn’t need as much working capital now as it did before. If the working capital is increasing, the Buyer may argue for a shorter lookback period because the business requires more working capital to stay on the current growth trajectory (which is likely a factor in the valuation). The reason most deals have a twelve-month lookback period is because most transactions are based on a multiple of the last twelve months EBITDA so it should take the average of the last twelve months adjusted working capital to deliver the last twelve months of EBITDA.

Once the Buyer’s diligence is complete, it will suggest a lookback period and provide an analysis of how they calculated normalized working capital. From there, the parties then either agree on the figures and analysis or they negotiate the lookback period or adjustments to working capital for GAAP adjustments, etc.

Example on Normalized Level of Working Capital

Impacts to Purchase Price in Example

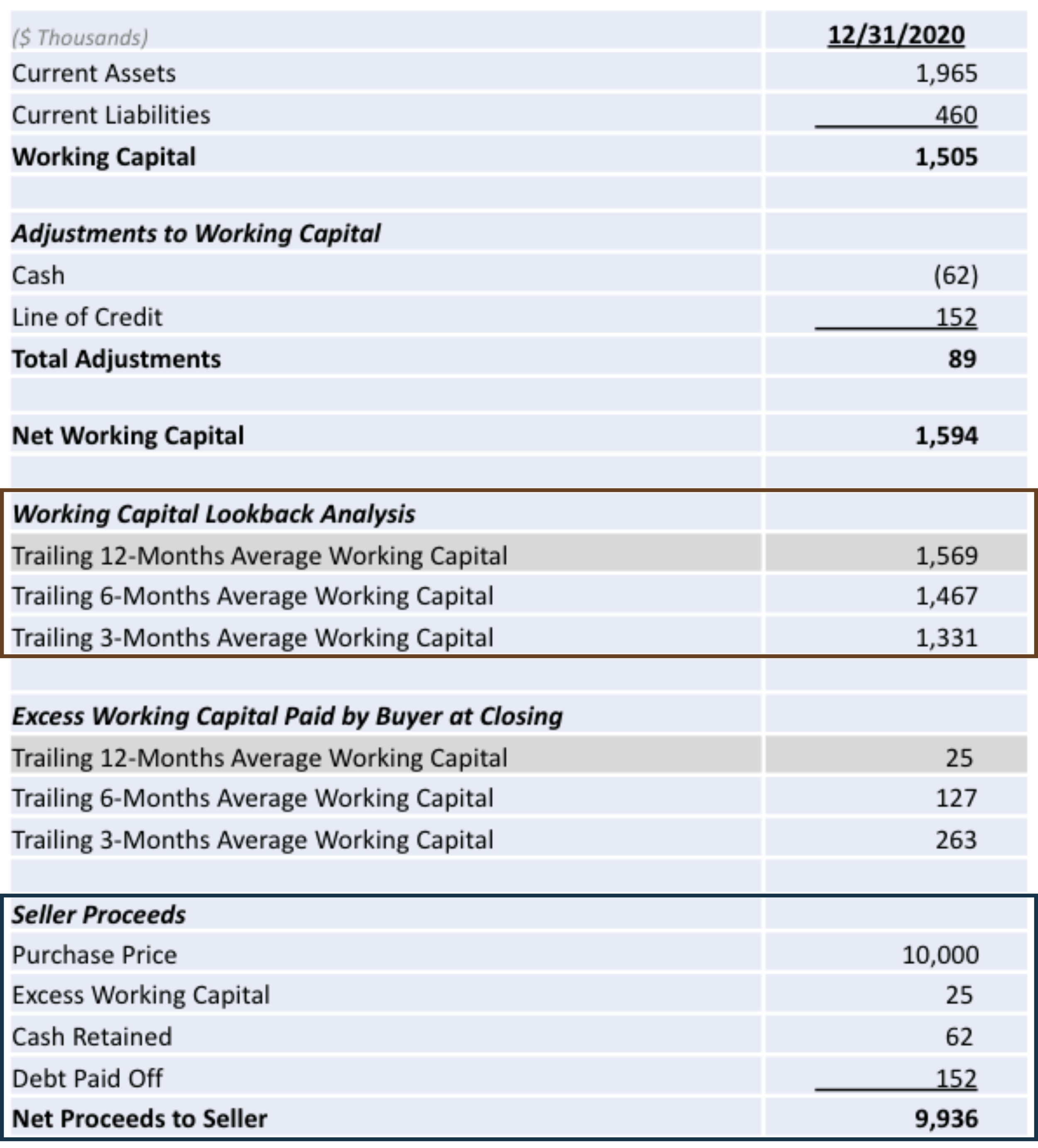

The unadjusted working capital estimate for the day of closing on 12/31/2020 is $1,505,000 which is calculated by subtracting the Current Liabilities from the Current Assets. However, because most transactions are structured on a cash-free, debt-free basis, those portions of working capital will not be delivered to the Buyer and must be considered Adjustments to Working Capital when calculating the Net Working Capital. The net working capital is $1,594,000.

In this example, the Seller will get paid for delivering more working capital than is “normal” or “average” regardless of how long the lookback period is because the Net Working Capital being delivered on the day of closing is higher than any of the lookback period averages. For example, if the parties used the typical twelve-month lookback period for the normal working capital, the Seller would be paid an additional $25,000 at closing for delivering “excess” working capital.

If the purchase price for 100% of the business on a cash-free debt-free basis was $10,000,000, the seller proceeds would look like the table at the left.